Representation Across City Sizes: Findings from Alberta’s 2025 Municipal Election

Under Alberta’s Municipal Government Act, a city is defined as a municipality with more than 10,000 residents, governed by a mayor and council, and characterized by higher-density development. Within that framework, this analysis examines how women and gender-diverse candidates fared in Alberta’s small, medium, and large cities in the October 20, 2025, municipal elections.

What emerges is a picture of uneven progress: improvements in some cities, stagnation in others, and a continued need for intentional support structures if parity is to become a consistent outcome rather than an isolated success.

A Snapshot of Alberta’s Municipal Landscape

To understand how representation varies across the province, Alberta’s cities can be grouped into three population categories:

Large cities (100,000+): Calgary, Edmonton, Lethbridge, Red Deer

Medium cities (30,000–100,000): Airdrie, Grande Prairie, Medicine Hat, St. Albert, Leduc, Spruce Grove

Small cities (<30,000): Beaumont, Brooks, Camrose, Chestermere, Cold Lake, Fort Saskatchewan, Lacombe, Wetaskiwin

These categories are not just demographic markers; they reflect different political cultures, expectations of councillor workload, and levels of visibility for candidates.

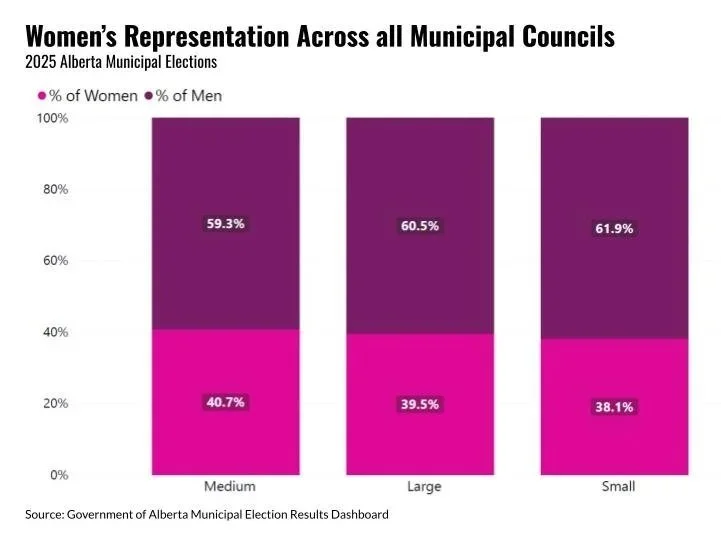

Across all city sizes, on average, women remain underrepresented:

Large cities: ~39.5% women councillors

Medium cities: ~40.7% women councillors

Small cities: ~38.1% women councillors

This produces an average of ~39% women’s representation across all municipal councils, noticeably below parity.

Key Trends

Medium cities are the strongest performers overall, with women representing ~40.7% of their city councils, on average. Several medium-sized cities (Airdrie and St. Albert) elected 57.1% women, demonstrating that parity-level outcomes are achievable at this scale. However, performance is inconsistent within the group. Grande Prairie and Medicine Hat elected just 22.2% women (for Medicine Hat, this represents a 45% decline from their pre-election council), creating a 35-point spread within a single category.

Large cities show the widest internal variation, and the extremes are stark. Calgary elected only 2 women out of 15 councillors (15.4%), the lowest percentage in the entire dataset. In contrast, Red Deer elected 5 women out of 9 seats (55.6%), closely aligning with or surpassing parity, alongside Edmonton at 53.8%. Lethbridge came in at 33.3%. This broad variability indicates that large-city outcomes are not uniformly better or worse; instead, they reflect differing political ecosystems, candidate slates, and competitive landscapes within each urban centre.

Small cities cluster within a narrower range, with most falling between 28.6% and 42.9% women councillors. This relative consistency suggests stable, though modest, levels of representation. Cities such as Fort Saskatchewan (42.9%), Lacombe (57.1%), and Wetaskiwin (42.9%) elected large proportions of women, while Beaumont, Cold Lake, and Chestermere elected under 30%. Notably, Lacombe was the only small city to surpass parity, electing 4 women and 3 men to council.

Mayoral results reveal even more pronounced differences across city sizes.

Large cities: 1 woman out of 4 mayors total (25%)

Medium cities: 3 women out of 6 mayors (50%)

Small cities: 3 women out of 8 mayors (~37.5%)

Again, medium cities emerge as the only group approaching a balanced outcome. Of the large cities, only Red Deer elected a woman mayor, former city councillor, Cindy Jeffries. Medium cities elected three, namely former city councillor, Heather Spearman (Airdrie), and incumbents Jackie Clayton (Grande Prairie) and Linnsie Clark (Medicine Hat). The three elected in small cities include former city councillors, Thalia Hibbs (Lacombe) and Lisa Makin (Fort Saskatchewan), along with Lisa Vanderkwaak (Beaumont).

Patterns & Persistent Gaps

Large Cities

The 2025 results reveal several persistent patterns across Alberta’s municipalities, with data showing that representation challenges manifest differently depending on city size.

In the large-city category, Calgary stands out most sharply: its 13–2 gender split is the lowest women’s representation anywhere in the dataset, underscoring how representation gaps can widen in highly competitive urban environments.

Larger electorates, higher campaign costs, and the need for extensive networks tend to favour established political actors, a group that still skews male. Yet representation in large cities varies considerably.

Edmonton, with a population of 1.19 million, elected a majority-women council (53.8%), while Calgary, the province’s largest city at 1.57 million, elected just 15.4% women. Meanwhile, smaller cities such as Red Deer (population ~113,000) outperformed both, electing 55.6% women, whereas Lethbridge (also ~111,000) elected 33.3%.

These disparities indicate that municipal size and campaign complexity alone do not determine gender representation; political culture, candidate recruitment, and local engagement remain central to driving more equitable outcomes.

Among the four large cities, only Red Deer elected a woman mayor, Cindy Jefferies, contributing to its strong overall representation of women. Yet this is not a universal trend: in Calgary, incumbent mayor Jyoti Gondek was defeated despite her visibility and experience. Taken together, these outcomes show that while women can and do succeed in mayoral races, their victories often remain contingent on local political dynamics.

Medium Cities

Medium-sized cities present a more textured picture. On one hand, places like Airdrie and St. Albert, each electing 57.1% women, demonstrate that gender parity is achievable at this scale. Their results suggest that mid-sized communities, with a balance of visibility and accessibility, can offer favourable conditions for a diverse slate of candidates.

On the other hand, the same grouping includes Grande Prairie and Medicine Hat, both of which elected just 22.2% women, a stark contrast. Notably, Medicine Hat’s representation plummeted from 67% in the prior council to 22%, marking one of the most dramatic declines in the province. This internal contrast makes clear that even among similarly sized cities, outcomes are far from uniform, and local dynamics remain decisive.

Mayoral outcomes tell a similarly mixed story. Three women secured mayoral seats in this category: Heather Spearman (Airdrie), and incumbents Jackie Clayton (Grande Prairie) and Linnsie Clark (Medicine Hat), indicating that existing office-holders or those with incumbent status can retain an advantage in executive races.

This variation suggests that the medium-city category is not inherently more equitable; rather, local recruitment practices, civic engagement, and the presence (or absence) of supportive networks heavily influence outcomes.

Small Cities

Small cities do tend to show a narrower band of representation, mostly falling between about 28.6% and 42.9% women representatives, but that pattern is punctuated by a clear outlier. Lacombe (57.1%) stands apart, having surpassed parity and elected a woman mayor, Thalia Hibbs.

Three women won mayoral races in small cities: Thalia Hibbs (Lacombe), Lisa Makin (Fort Saskatchewan), and Lisa Vanderkwaak (Beaumont). Notably, Hibbs and Makin previously served on city council, suggesting that candidates with existing public profiles or prior municipal experience may hold an advantage in executive races.

However, political recruitment in many smaller communities still often happens informally through personal or professional networks that remain predominantly male, narrowing the pipeline of potential women candidates. Where those networks are broader or where active recruitment occurs, however, small cities can and do produce strong gender-balanced outcomes.

Barriers Behind the Outcomes

Though each community operates within its own political culture, several province-wide factors help explain why representation remains uneven.

Many municipalities lack formal recruitment or nomination mechanisms, leaving candidate pipelines dependent on informal networks that often overlook or under-encourage women. Gendered expectations around leadership, including perceptions of likability, readiness, and “fit” for public office, can further deter women from running or shape voter attitudes once they do.

At the same time, the visibility of women who are elected in 2025 has the potential to shift these dynamics. When women see peers leading and succeeding in their own communities, it can expand their sense of possibility, encourage more to step forward in future cycles, and strengthen the networks that support their campaigns. Progress may not be linear, but representation can be self-reinforcing: each woman who wins office makes space for others to follow.

The 2025 outcomes show that progress is possible but fragile, influenced by who chooses to run, who receives support, and who sees themselves reflected in political leadership. Yet several municipalities demonstrate what meaningful gains can look like in practice. Airdrie and St. Albert each elected 57.1% women to council, showing that strong representation is achievable in mid-sized cities. Red Deer likewise reached majority representation at 55.6%, and Edmonton elected 53.8% women, joining the ranks of large cities with women-majority councils.

These examples illustrate that gender-balanced leadership is not hypothetical; it is already happening in communities of different sizes and political contexts across the province. Sustained attention to recruitment, mentorship, and reducing informal barriers can help ensure that these gains are not only achieved but also maintained. With consistent commitment, Alberta’s municipal councils can continue to evolve to accurately reflect and serve the people they represent.